As a coach I love ‘guinea pigging’ myself. If I want to know what a session feels like for an athlete, then I often go out and do it myself. It’s one thing to know what the prescribed rest:recovery ratios are in the scientific literature. But it’s another thing entirely to go and do the session yourself to remind you what it will feel like.

So it comes to be that I guinea pigged myself again this weekend gone. Not in a training session, but in a race. I’d been asked some time ago to fill in for a friend and do the bike leg in a team for the Hervey Bay 100 triathlon (affectionately known as the Hundy). I hadn’t raced in this event before, and I thought it would be fun. What’s not to love about an 80km ITT after all?

My racing season on the road is over, so it’s back into base miles for me. This means nice long Saturday rides with lots of elevation. I wasn’t really keen to give up this Saturday ride in order to have fresh legs for the Hundy. So I decided to do my long and hilly Saturday ride as normal, and race the Hundy on cooked legs. I wanted to know how much (if any) difference this would make. The answer is, quite a bit indeed.

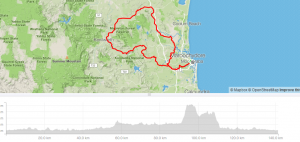

To the background – here is the Saturday ride. It was done in a smallish group of 8 pretty solid riders. There was no mucking around, just head down and get to work. The ride also included what many regard as the hardest climb on the Sunny Coast – the Obi range. A nasty climb of just on 3kms with some sections close to 30% gradient. It’s part of the course for Velothon Sunshine Coast, and has reduced many riders to walking.

Summary stats

- Distance: 141km

- Elevation: 2035m

- Average Speed: 30.1

- Normalized power: 148W (on a FTP of 200)

- TSS – 351. This is the key metric. I regard any ride with a TSS of higher than 300 as being significant training load. It’s kind of my bench mark for trying to achieve breakthroughs in riders. A ride of this magnitude will increase your chronic training load markedly. In this case mine went from 108 to 114 in one ride.

Suffice to say my legs were cooked after. It was a fabulous fun ride with great mates though, so was well worth it!

I drove the 200km to Hervey Bay on Saturday afternoon to meet up with my team mates who I didn’t know. Both of them are legends of surf ironman, Hayley Bateup and Britt Murray (nee Collie). That made me feel a certain amount of pressure to ride well and not let them down. So I was mighty relieved to find them at their campsite drinking wine, eating cheese and laughing their heads off. Phew, pressure off. But heck there is a white line so you are always going to race aren’t you?

Sunday race morning – for those interested and who use Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and the app to monitor their training and recovery. I measure my HRV as soon as my alarm goes off. And you got it; based on my Saturday ride the recommendation from the HRV4 training app was to keep intensity low as I was not fully recovered. This was going to be interesting.

Britt was doing the swim and told me she was ‘not very fit’. But if there is one thing I know about swimmers, it is that even when they are not fit they still swim well. So I was not surprised when she got out of the swim in first place for the female teams and 4th place in teams overall. No pressure.

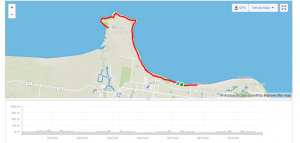

Headed out onto the bike course, which was 4 laps of 20km, very fast and flat. There was only a tiny little kicker climb, giving a total elevation on course of around 250 metres for the 80km.

Now here’s the bit I actually was interested in and why I wrote this blog. The athletes I work with all know that I coach on the interplay between cadence, power and heart rate. All are extremely important metrics. I know some might say that once you have a power meter you don’t need to look at heart rate. But that is absolutely untrue. The best value from a power meter comes with looking at what your heart rate does at different powers and on different cadence. It’s the interplay between central (cardiovascular) load and peripheral (metabolic or muscular load).

Typically when you ride at a lower cadence you can generate more power and your heart rate will be lower. But this can come at a price. For triathletes it can mean that their legs are over-loaded before the run. Some triathlon coaches work only on low cadences and teach their athletes how to adapt their position on the bike to save their legs for the run. At certain times of the training cycle I absolutely agree with this approach. But at other times of the training cycle (i.e. – base training) I disagree with this approach as higher cadence workouts produce cardiovascular adaptations that cannot be gained through any other form of training. But I digress, and that’s another blog.

Based on my knowledge of my own physiology, my plan was to ride at a cadence of about 80. In terms of power, the normal recommendation I make for a half ironman triathlete is somewhere between 80 and 85% of FTP. But that is knowing that the athlete needs to get off and run. I don’t need to do that as I am only doing the bike leg, so theoretically I should be able to hold more than this; closer to 90% of FTP. This placed my target power at 162 to 171 watts at an average cadence of 80. Now those of you that are observant will say, hang on Deb, if your FTP is 200 then your target power at 90% should be 180W. Correct. But I do my FTP tests on a 3% gradient, and I know I can’t hold the same power on the flat, hence the lower target figure.

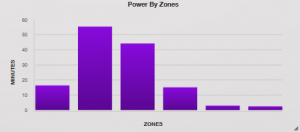

So what happened? As soon as I started riding my legs were talking to me. And not in a nice way. I thought to myself, give them a chance to warm up and they might shut up. They didn’t. I simply could not ride at a cadence of 80. I could feel this and intuitively upped my cadence to protect my legs. But of course this meant that I could not generate the power that I wanted. My average power stubbornly sat in the low 150s. This is pretty much Z3 tempo riding for me, but it was all I could muster. Here is the power zone profile, and it’s absolutely not what a coach would want to see for an ITT or a triathlete on a flat bike course.

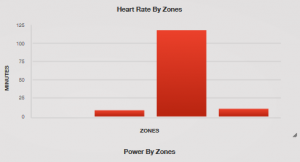

But now here is the interesting thing, and the point I most want to make on this. Normally when you ride a higher cadence your heart rate increases to reflect this. Mine didn’t. It also sat stubbornly in Z3 for almost the entire race. I could not get it to even approach moving into threshold territory. It was only toward the end of the race, with a bit of cardiac drift that it moved into Z4. This suppression of the heart rate response is very typical of athletes in a heavy training block, or following a tough session. It’s the reason why you still need to consider what your heart rate is doing once you have a power meter.

In my head I kept saying to myself, just keep your rhythm and you’ll be OK. And I was, albeit at a lower power than I wanted. The average speed in the end was OK, at a smidge over 35kph. But I averaged more than 37kph last year in a team half ironman ride, and I am fitter now than I was then. My guesstimate is that on fresh legs I should have been around 38kph average for this course.

The summary stats in the end – average power 156, average cadence was 89, average heart rate 156 (threshold is low 170s).

What are the take home messages from this:

- My feeling is that the limiting factor were my legs (peripheral) and the metrics support this. However, there was also a central suppression in heart rate indicating that I had not recovered from the week’s training, full stop.

- In stage races, road riders have to back up day after day with hilly climbing stages. I felt like I could have done a hilly road ride. But the metronomic nature of a fast and flat time trial course was physiologically very different. In triathlons and time trials on flat courses you need to get into a rhythm and pound out the watts. Every time I tried to increase power through lowering cadence my legs would start to cramp through the adductors. So it was a case of the specific requirements of the event not being able to be met.

- Generally speaking, it would take 48 hours for your legs to recover from a 300+ TSS ride.

- Overall, I don’t see a role for training like this other than for psychological reasons (i.e. – it’s fun to be in a team). You need to go into the race knowing that you have not backed off for it, and will perform accordingly (or not perform so to speak).

Fortunately I was carried by a great swimmer and a great runner in Hayley Bateup who cranked out a run time of 84 minutes. We took out the win in women’s teams and were 8th overall from 75 teams. If you haven’t done the Hundy I highly recommend it. It’s a real ‘old school’ triathlon, untouched by the commercialism we see in so many events now. Heck, I’m old school, I loved it. Thanks to my team mates for a great weekend.

0 Comments