Wow, what a weekend! For many amateur Australian cyclists the peak event of the year happened on Sunday – Amy’s Gran Fondo. This spectacular event is held in the picturesque Victorian coastal town of Lorne. Spanning 122 kilometers with 1800 meters of climbing, the challenging course has been part of the UCI Gran Fondo World Series for many years. This year it took on even greater significance, as a qualifier for the 2025 Gran Fondo World Champs which will take place on the same course.

More than 4000 riders registered to take part. For many, they were chasing a top 25% finish in their category in order to qualify for Worlds next year. The ride also afforded the opportunity for athletes to familiarise themselves with the course, and the race dynamics that may well play out on the day next year.

At Spin Doctor Coaching, we had 15 athletes tackle the course, including two full time coaches. As such the file analysis post event was a nirvana of data, offering a wealth of insights. What did we learn about the demands of the race, and how does this shape the preparation of our athletes moving forward? Here, we share some of that information.

The Weather

It would be remiss of us not to at least comment on the weather conditions that Victoria dished up for us. The day before the race was bleak. Cold, wet, windy. There was rain. There was hail. There was sleet. There were a lot of antsy athletes who wanted to get out and ride a recon up the climb, but decided the weather was too grim for that. A few brave souls ventured out. Some regretted that decision, others didn’t. But most of us spent the night praying to the weather gods as we listened to the wind howling. Fortunately race day presented better conditions. Though it was cold waiting around and for some; challenging to know just what to wear with a 10km climb to start the race. Most riders opted for an under shirt, arm warmers and plenty added a gillet.

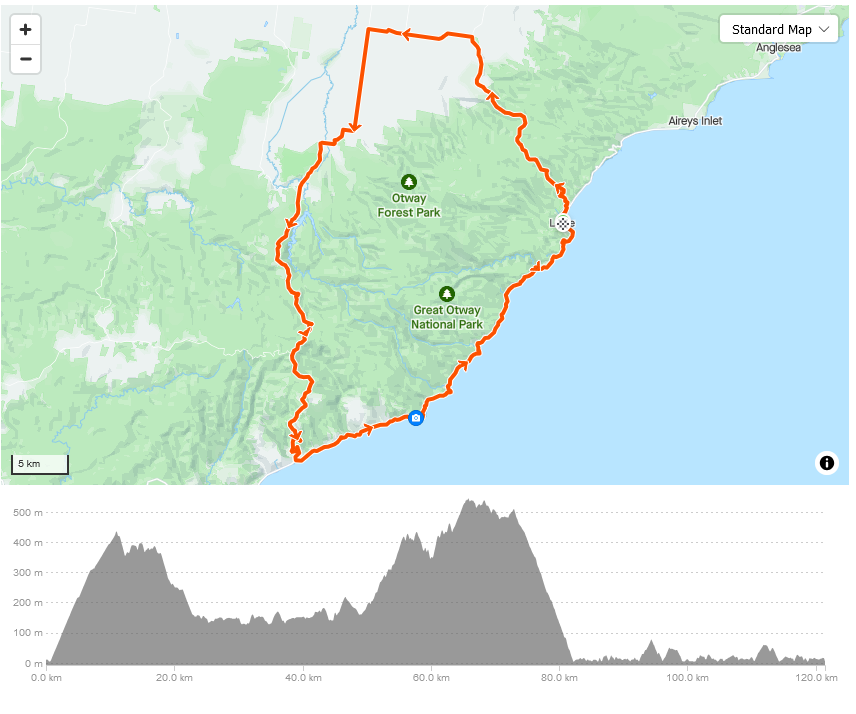

The Course

Let’s start by talking about the course. It’s relevant to point out that both of our full-time coaches that raced were already familiar with the Amy’s course, having done it a number of times before. The profile is shown below. Right from the start is the famed Benwerrin climb. It’s 10km with an average gradient of 4%. It is steepest at the beginning, and has a couple of saddles, and finishes with rollers. Following the descent there is a flattish section from the 20-50km mark. Then starts climb 2, but this happens in two sections. The first is 6km at around 5% gradient, a descent, then another 4km with a similar gradient. All up it is 15km with 350m of elevation. Then comes the most fun of the ride for many. A super fast 10km descent that brings you back to the Great Ocean Road. A left hander to end the descent, and you commence a 40km run in along some of the most magnificent coastline of Australia. There are a few rollers in this section, but largely it is reasonably flat.

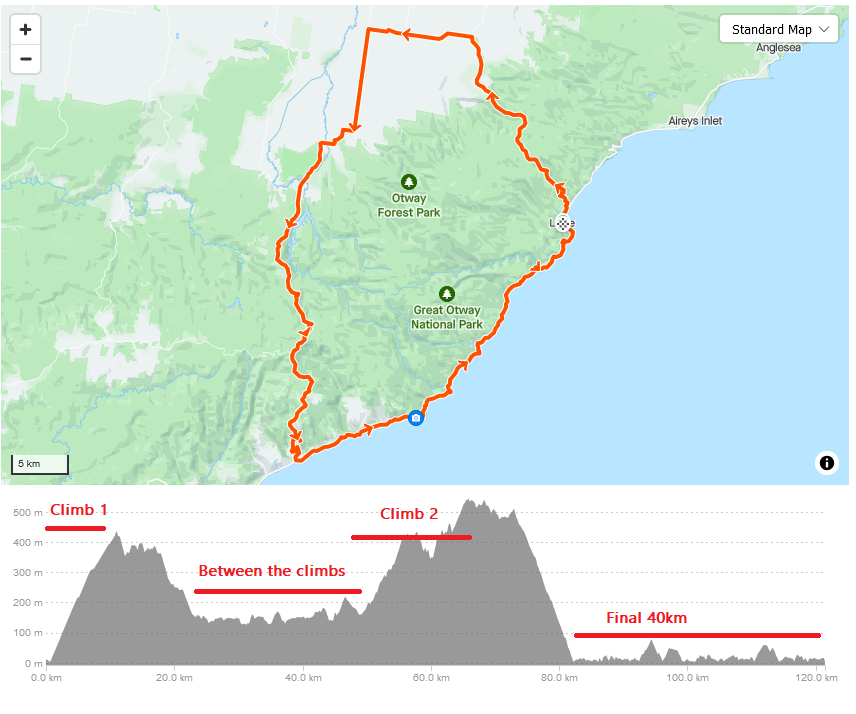

Ok, so what did we learn from the data and the race. For analysis purposes for our athletes we broke the race up into sections. These are marked below – the first climb, the sections between the climbs, the second climb, and the run in along the coast for the final 40km.

The Start

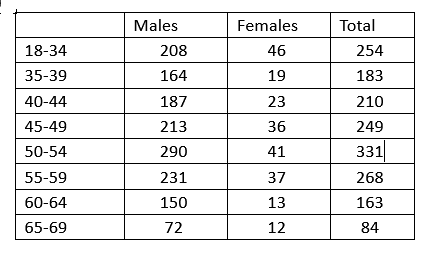

Riders started in waves based on their age. Younger riders went first with male and female riders together. That is 19-34 riders went first and were together. Does this change the dynamic of the race for female riders, you betcha. More on this later. How big were the waves? Pretty jolly big. Based on finishers the numbers were as follows (add on a few for DNFs in each category, DNS not included, recreation riders not included as they started later). As is usually the case with Gran Fondos, the biggest numbers were in the middle male masters age categories.

There were marked areas for each wave with the men and women combined in that category. As one wave rolled off the start, the waiting riders were allowed to move up to the starting line. The time difference between waves was quite short at 2 or 3 minutes. The first 2km was listed as a neutral zone, with the official timing starting part way up the climb. We can confirm that it definitely was not ridden as neutral. Riders were negotiating for position in this 2km and trying to set themselves up for the climb. The pace was not controlled by the lead vehicles at all. Who knows if this will be the case for Worlds next year. But it needs to be something you pay attention to. It was hard for riders to know where the lead bunch of their group actually was. Many were not aware that there were riders up the road and thought they were in the lead group for their age group.

It’s also worth mentioning how this start impacts the female riders. Again, it is not yet listed for Worlds 2025 if men and women will start together. What we do know is that there is no medio fondo course planned for 2025. This means all riders, regardless of age, will ride the same course. One would imagine (hope) that there will be separate waves for men and women. But if there is not, the dynamics will play out as they did this year at Amy’s. That is, the women will be mixed in amongst the men. This affords the women the opportunity to utilise the larger bunches of male riders to formulate their tactics. This is an area we paid particular attention to with our athletes in developing their race plan. For some of our female riders, the addition of men worked to their advantage. For others, it did not. That is Fondo racing though, and female riders need to be open minded about this.

The First Climb

What is really clear from our data is that the first climb was absolutely crucial in setting up the race. W/kg up the first climb was the single best predictor of race result for our athletes. And it accounted for a LOT of the variance in performance. And we mean a LOT. Of course that makes sense. If you are at the top of the hill with stronger riders, then you are going to be with a stronger group for the crucial 40-50km section between climbs. And a stronger group is going to go faster and set you up well for the second climb.

What sort of power should you be able to hold on that first climb? The answer, as always, is that ‘it depends’. But for riders in that 25-30 minute range (and that was a lot of riders) you should be able to hold close to your FTP. Faster riders should be able to hold a higher percentage of their FTP. We specialise in masters level riders and many of our athletes have FTPs in the range of 3.5 to 4.5W/kg. The average intensity factor for our 15 riders up the first climb was 0.98. That is, they held 98% of FTP up the climb. The range was 0.92 to 1.05. This completely lines up with our expectations with the more capable riders riding at a higher percentage of FTP than those with lower W/kg, who took longer on the climb.

One of the really clear things with our data analysis is how important the first 5 minutes of the climb was. All of our riders but one set their highest 5 minute power for the whole race in the first 5 minutes of climb 1. This is despite the fact that much of this climb was designated ‘neutral’ by the organisers. It was anything but neutral. What is the learning from this? You need to be prepared for a ‘hard start’. How hard you ask? About 110% of FTP is the answer. On average for our riders the intensity factor over this 5 minutes was 1.09 with the range being 1.01 to 1.13. We have also done a fair amount of Strava stalking of podium winners; and can confirm that the pattern was the same for these riders as well.

Between the Climbs

This was an interesting area of the race where group dynamics played an important role. Riders that had been separated on the first climb managed to be swept back into other groups, and larger groups were formed and re-formed in the middle of the race. At the front of the race the small packs that had formed kept the pace higher, in order to maintain the gap they had established at the top of the climb. For this reason we saw a bit more variability in the intensity that riders held for this section of the race. The overall Intensity Factor for our 15 riders here was 0.83; but the range was 0.76 to 0.95. The lower numbers were from riders who were in large groups and surfing their way along. They knew it was pointless to try and go off the front of the group they were in, and were saving themselves for the next climb. The higher intensities were from riders who were trying to bridge across to a group, or stuck in ‘no man’s land’ for some of this section. It’s not a place you want to be. We also saw a fair amount of heart rate recovery on this section for some of our riders, especially those that managed to be in larger groups.

The Second Climb

This was an area of the race that as a coaching group we had focused on a lot, as we knew it was going to be important. Fatigue resistance (some call it durability) starts to come into play. Stronger riders will have done more than 1000kJ of work by this stage, and at a pretty high intensity. The ability to hold power for this extended climb was crucial. For riders in the 3.5 to 4.5W/kg range this section took between 35 and 45 minutes. The average Intensity Factor for our riders here was 0.89 with the range being 0.80 to 0.94. The stronger riders all held 0.90 or above. Again our Strava stalking of podium finishers shows a similar pattern. Given the longer length of time taken to complete this time, the lower intensity when compared to Climb 1 makes sense.

The Descent

Before we start with the final 40km, we should mention the descent. Of course the power numbers here are not relevant, as it mostly comes down to descending skills. What a treat it was to have a closed road and the whole width of the road to work with. Because of the nature of the packs that form on the final 40km, it’s crucial to descend well and hold position with the group you are with. On average this descent took riders toward the front of the race between 9 and 10 minutes. Descend even 30 seconds slower than others and you will find yourself in a different group at the bottom of the climb. Or worse still, dangling in no man’s land between groups and watching the tantalising close group in front ride off despite your best efforts to bridge across (the author might be speaking from experience here).

The final 40km

This is a section of the race that many riders look forward to. A beautiful and relatively flat 40km along the famed Great Ocean road. The ocean is to your right and the wind is often a southerly. So a cross wind but in this case it was a cross tail wind home. There are a few rollers and little pinches to test the legs out here. And if you are going to cramp, this is likely where it will occur. You stand up and ask your legs a question, and sometimes they come back to you with an answer you do not want!

The average Intensity Factor for our riders on this section was 0.81 and the range was quite wide at 0.75 to 0.92. Some of the lower numbers were from riders who were in largish groups. However to be fair, some of the lower numbers were also from riders who were absolutely cooked. The higher numbers were from riders who were trying to bridge across to faster groups, or working hard rolling turns in smaller groups. There is a little bit of luck involved with this, but of course we have some control in creating our own luck.

Overall thoughts

Here are some final metrics overall which are enlightening.

Average Intensity Factor for the total ride for our 15 riders: 0.85 (range 0.79 to 0.92). This means on average our riders had a Normalized Power which was 85% of their FTP for between the 3 and 4.5 hours it took them to complete the race. This is a very solid intensity and shows just how hard this race is.

Average Training Stress Score was 281 with a range of 230 to 371. We need to have total respect for the riders with the higher TSS. Many of them were working at the same Intensity Factor as the faster riders, but for much longer!

It’s key to look at Time in Zone , specifically the amount of time spent in zones 4, 5 and 6 on this ride. Zone 4 being threshold, Z5 being VO2 and Z6 being anaerobic. We analysed this for all our athletes. There is a consistent pattern to the results. Zone 4 is the money zone. Holding power at this intensity is crucial. There is less time in zones 5 and 6 than you might have thought. On average most athletes spent about the same amount of time in Zone 4, as Zones 5 and 6 combined.

We’ve looked at W/kg and absolute FTP (not relative) as predictors of race performance. We’ve already alluded to the fact that W/kg accounts for a huge amount of the variance in performance. Much more than absolute FTP. This will be guiding the strategies we use to prepare our athletes moving forward for Worlds next year on this course. At the moment we have 11 qualified and expect to add a reasonable number to this through the Tour de Brisbane qualification race in April next year.

One of the things we have not discussed here is fueling. It is crucial, and cannot be separated from the training process. It is an area that we work on continuously with athletes. We periodise our athlete’s fueling plans, just as we periodise their training. There is a lot of talk at the moment about the ‘carbohydrate revolution’ in cycling. It is not a revolution. It is something that our group has been doing for years, based on scientific evidence and field testing. All of our athletes have a bespoke fueling plan for both training and racing that is dialed in and refined well ahead of the event. This plan is based on the projected intensity and work output expected. It is possible to estimate this relatively accurately using a power meter and TrainingPeaks if you have knowledge of an athlete’s FTP and expected work rate. For Amy’s this would be in the range of 2500 to 3000kJ at the point end of the field.

Another area that we have only touched on briefly in this blog is that of tactics. All our athletes had a pre-event meeting before Amy’s where we went over expected tactics. It starts with course analysis; knowing the demands of the parcours. This is overlaid with competitor analysis and knowing our rider’s strengths and limiters in order to come up with a race strategy that best suits the individual rider.

As we wrap up this year’s Amy’s Gran Fondo, the real work begins—not just for the riders, but for us as coaches. Through detailed analysis of rider data, from pacing strategies to power outputs and heart rate trends, we’ve gained valuable insights into what works on a challenging course like this. The 122 km with 1800 meters of elevation has provided a wealth of information that will guide our training programs moving forward.

This year’s data has sharpened our understanding of how to tailor training plans that optimize performance on race day, helping riders achieve their personal bests. Whether you’re targeting a world championship qualification/result, or simply improving your endurance and climbing ability, our analysis allows us to create more personalized, effective training regimens.

If you’re ready to elevate your cycling performance and learn from the insights we’ve gathered, we have coaching spots available. Join us, and let’s start preparing together for your next big race!